Maida Vale is renowned for the mansion blocks that line its broad avenues and give the area a very distinctive and quite European feel. The land was owned by the Church Commissioners who resisted development until the late 1890’s. By this point, mansion blocks, rather than houses, were the most profitable option.

Ashworth Mansions in 1910

Some argue that Romans were living in flats as early as 455BC but the more recent history of appartments starts with the citizens of Paris and Edinburgh. Hemmed in by old city walls the inhabitants of these two cities began living horizontally from the 1700’s. In contrast, London was a peaceful and fast growing metropolis free from its medieval confines. Its rich and fashionable classes increasingly preferred to live outside the old walls of the City and built their houses on the surrounding fields and market gardens. In London, apartments remained the preserve of the poor until the last days of Queen Victoria’s reign. The middle classes, set on keeping up appearances, would not settle for less than a house and garden in one of the burgeoning suburbs, even if this meant a lengthy commute to work.

First Flats

The first apartment buildings appeared in the 1860’s along Victoria Street but were not a great success. Many thought flats harboured infectious diseases, others worried about burglary and the better class of servants refused to work in them. Worse, flats were associated with the French; and that meant loose morals and poor personal hygeine. As one contemporary architect put it “The French use very little water, believing they can wash themselves with the corner of a wet towel.” And the very idea of having bedrooms on the same level as the reception rooms was clearly an invitation to promiscuity.

Often built as speculations by builders in a hurry to complete the job and pay off their investors, flats also suffered from poor noise insulation, “useless ornament, hideous cornices and plaster work that had far better be omitted.” By far the largest early block, the 14 story Queen Annes’ Mansions (shown left) on Queen Annes Gate, was universally revilled as hideously ugly and contributed to the rather snooty attitude towards flats held by the architectural establishement.

Often built as speculations by builders in a hurry to complete the job and pay off their investors, flats also suffered from poor noise insulation, “useless ornament, hideous cornices and plaster work that had far better be omitted.” By far the largest early block, the 14 story Queen Annes’ Mansions (shown left) on Queen Annes Gate, was universally revilled as hideously ugly and contributed to the rather snooty attitude towards flats held by the architectural establishement.

As it turned out, Queen Anne Mansions was a roaring commercial success. Even so, by the mid-1880’s there were probably still less than twenty middle class blocks in all of London. Most were aimed at single men, and many were not properly flats as we would understand them at all, but a cross between a flat and a hotel known as “catering flats”. In this model, a gentleman would rent a suite comprising a sitting room and bedroom but take all his meals in a communal dining room. Two of the most successful examples were Whitehall Court (now the Thistle Hotel and National Liberal Club) and Hyde Park Court (now the Mandarin Oriental), both designed by the architectural practice Archer and Green, in whose chambers worked the young Edward Bohemer and Percy Gibbs, the future architects of Ashworth Mansions.

Flat building in London did not seriously begin until the late 1890’s when the demand for affordable accommodation within easy reach of work and nightlife began to over-ride middle class misgivings.

Two main factors caused this change of heart. The first was that there simply were not enought servants to go round. By the late 1890’s, almost 16% of the entire UK population was in domestic service and universal public education was beginning to reduce the supply of unskilled young girls willing to put up with the long hours and poor working conditions. Meanwhile, the startling growth of professional people (up by more than 50% in the twenty years to 1901) increased demand for hired help. Consequently, wages rose and servants became both more expensive and more demanding of their employers. Two servants were normally required to maintain a professional couple in a house; flat dwellers could happily make do with just one. And “the mistress would have more control over her servants, than in a private house; in other words there was no “back door”.

Moreover, London nightlife was becoming more respectable. A visit to a theatre was no longer synonymous with debauchery and dining out no longer the preserve of the aristocracy. With so much fun to be had in town, a growing number of the new professional classes were unwilling to curtail their social lives by moving to suburbia. They were in the market for affordable accommodation within easy reach of the bright lights of the West End.

Development of Maida Vale

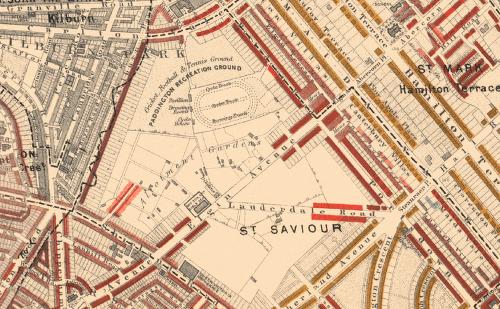

The Church Commissioners, who owned the land north of Regent’s Canal as far as Kilburn, were determined that their estates should be solidly middle class and preferred to leave land undeveloped rather than risk the wrong sort of tenants. St Peter’s Town, the area west of Shirland Road, had quickly gone down hill as it became overrun by lodgings and stabling for the cab drivers servicing Paddington Station. The Commissioners were adamant that was not going to happen in Maida Vale. Building was halted during the recession of the 1880’s (see the map below from 1885) – meaning that flats (not houses) would be the most profitable development when the market picked up again in the late 1890’s. Unhappily for the commissioners, this pause in development allowed the preservation of a large chunk of the estate as Paddington Recreation Ground. The commissioners fought hard to build flats on this too but fortunately a high profile public campaign thwarted their ambitions.

Victor Gollancz, who lived as a child at 258 Elgin Avenue, directly opposite where Ashworth Mansions now stands, recalled that “from a point a few houses further down than ours up to a point not far short of the Paddington and Maida Vale High School [now City of Westminster College] there was a gap in what would nowadays be called the built-up area, given over to ups-and-downs, fields with clover in them and market-gardens. ..

The market- gardens pleased me more, particularly in the autumn, when enormous multi-coloured dahlias sparkled like the morning dew…. As for the ups-and-downs, these were small hillocks and valleys on either side of the road where pavements ought to have been: I spent a lot of time running up and down them ….”

When construction resumed, in the late 1890’s, flats offered better yields than houses and were now respectable enough to satisfy the Commissioners.

In order to make it clear that these residential buildings were properly middle class, the blocks of flats were called “mansions” and given external trappings of elegance. Ashworth Mansions was the first block built on Elgin Avenue and endowed with a grand carriage drive, copper cupolas and stained glass. Marketing emphasised the convenience and modernity of the apartments including electricity and telephone.

Charles Booth, prowled around Maida Vale in January 1900 classifying London streets for his famous poverty map. The area was in the midst of the flat building boom with streets “inches deep in mud”. He reported that “the demand for flats seems to be insatiable” particularly amongst rich Jews looking to live close to the Synagogue. Essendine Mansions was “tenanted as soon as ready by a theatrical class, actors and actresses. Respectable.”

The architects Bohemer and Gibbs were responsible for the three blocks on Elgin Avenue – Ashworth Mansions, Biddulph Mansions and Elgin Mansions. They met while they both were working in the chambers of Archer and Green, the designers of some of the first and boldest blocks of flats in London. The young Bohmer and Gibbs cut their teeth on the “fanciful palaces” of Whitehall Court and Hyde Park Court in Knightsbridge which was one of the sights of London when it opened in 1890. The early French renaissence was a strong influence and echos of the Chateau de Madrid, built in the early 1500’s at Neuilly by Francis I can be seen on the Elgin Avenue frontage of Ashworth Mansions.

Whitehall Court and Hyde Park Court (now the Mandarin Oriental Hotel) were financed by Jabez Balfour, the notorious fraudster, whose role in the collapse of the Liberator Building Society cost him 14 years in prison.

With their principal client in gaol, Archer and Green dissolved their partnership and the young Boehmer and Gibbs struck out on their own. The pair soon became some of London’s most prolific flat builders, often working for the master mansion block developer Edward Jarvis Cave, of which more later . Beginning with the triumvirate of Vale, Blomfield and Aberdeen Courts which bring a touch of Parisian glamour to the end of the Edgware Road, Boehmer and Gibbs went on to construct the three Elgin Avenue blocks, Lauderdale Mansions, Delaware Mansions (also in Maida Vale), Marlborough Mansions on the Finchley Road, the BAM estate in West Hamstead, Iverna Court in Kensington, Strathcona Mansions on Marylebone Road and Lissendon Gardens in Camden. Percy Gibbs died young of a brain tumour. Boehmer continued in practice on his own until his death in 1940 with notable buildings including Harley House in 1904 and the German Lutheran Church in Brompton.

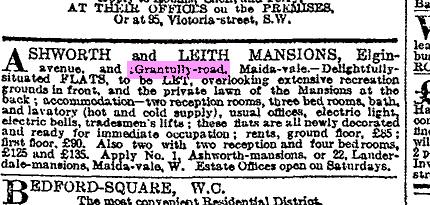

Ashworth Mansions itself was built in two stages with Edward Bohemer supervising from his flat at 10 Lauderdale Mansions. The Elgin Avenue block was constructed first and occupied in 1899 and the Grantully block in 1900. Almost all the flats were occupied by 1902. A contemporary advertisement boasts of “landscaped gardens, hot and cold water, electricity, electric bells and tradesmans’ lifts”. A ground floor, three bedroom, flat cost £85/year with first floor ones £5 dearer. Four bedroom flats were £125-£135. To put this in context, a typical live-in maid earned £40 per year and a good horse could be purchased for 50 guineas.

Boehmer and Gibbs were well aware their responsibilities to maintain property values and stated in one planning application “there is not the slightest vestige of possibility of [these flats] ever becoming tenanted by Artisans or the Working Classes’.

Financial considerations were, of course, paramount to the builder, architects and financiers that carpeted London’s inner suburbs with mansion flats in the years until 1910. A well-run block with good tenants could make a solid investment return of 7%-8%. But the real money was made by the risk-takers who borrowed to build the blocks in the first place with a view to selling them on a long-lease as soon as possible after completion.

Foremost among these risk-takers were the Cave family, a dynasty of speculating builders that worked closely with Boehmer and Gibbs and were responsible for Ashworth Mansions among many others. Edward Cave was born in Leicester but made and then lost his fortune in London. Beginning with just £100, he played a critical role in developing middle class flats and was responsible directly or indirectly for most of the blocks in and around Maida Vale and West Hampstead. By 1889 he was promoting a company to buy up a number of pubs and restaurants including the Angel, Islington. In 1898 he was raising money for the Hampstead Electric Supply Co – which was supplying over 500 houses by this time using his new blocks as captive customers.

Cave was a sharp operator. In 1895, he worked with Boehmer and Gibbs to build a row of shops on Kensington High Street. The client was Jubal Webb, a celebrity cheese-monger. Webb was a showman who had exhibited the world’s largest cheese at the Chicago World Fair in 1893 and whose address for telegraphs was ‘Gorgonzola London’. Webb asked Cave to insert a restrictive covenant explicitly forbidding any other cheese seller from taking one of the premises. Cave persuaded Webb that such a clause was not necessary and then promptly sold one of the leases to Hudson – a rival cheesemonger. Jubel Webb sued. And lost.

Edward Cave went bankrupt in 1900 with liabilities of over £500.000. Throughout his career, he had built with borrowed money. Things began to go wrong in 1896 with the development of Broad Street House in the City. Cave was forced to sell this development at a loss and was also hit by a failed attempt to rebuild the Black Lion pub in West Hampstead. Then, having overbuilt, he couldn’t find tenants or purchasers for a number of his appartment blocks. Though his fortunes declined, Edward Cave kept on spending. His personal outgoings were a prodigious £4.000 a year. This included a house at the seaside, a share in a shooting box, expenses to maintain various ladies under his protection and, for his amusement, a 375 acre farm in Hampshire. At the time of his bankruptcy he was building a mansion for himself in Hampstead complete with stables and vineries.

Edward Cave’s financial collapse also brought down two of his sons. Henry Jarvis Cave built Lauderdale Mansions in which he lived. But he could not let the flats at high enough rents and was declared bankrupt in 1903. Henry stayed trading a little longer than his brother Edward Athelstan Cave whose “rash and hazardous speculation and unjustifiable extravagance in living” forced both bankruptcy and a move from his Hampstead mansion to the comparative squalor of Flat 57 Biddulph Mansions.

Edward Cave’s daughter, Florence, was rather more fortunate. She won the figure skating gold medal in the 1908 London Olympics under her married name of Madge Sayers.

Cave sold the lease on Ashworth Mansions and some other blocks to Harry Charles Costello Shaw, doctor turned property investor. Shaw kept a close eye on his flats but was much too grand to live in an apartment, instead residing in a splendid villa at 125 Maida Vale with his large family and five servants.

After the bankruptcy, the Cave property empire was packaged into a new company called Mansions Consolidated Ltd which operated a number of blocks in Hampstead, Highgate and Maida Vale, including Ashworth, Biddulph, Elgin and Lauderdale Mansions. Mansions Consolidated, itself, went into liquidation in 1910 but did not disappear without trace. Notably, it made a major contribution to the financial ruin of its chairman, Dan Harries (DH) Evans, the department store magnate, who was finally declared bankrupt in 1915. DH Evans founded his store on Oxford Street in 1879 with just £1.500 and sold it, just fifteen years later, for £160.000. Once a wealthy man, DH Evans died in penury having lost all his money speculating in London property. Mansions Consolidated cost him, personally, £65.000.

Mansions Consolidated also left its mark in property law due to a test case at Lauderdale Mansions that is still cited today. Frederick Jaeger, tenant of flat 161, complained that some other apartments were being used “as places of meeting between men and women for improper purposes.” He refused to pay his rent as his quiet enjoyment of the property was being interfered with. The judge ruled that the landlord was not responsible for any disturbance caused by other tenants unless this had been actively encouraged by him.

Maida Vale

“If you live in Maida Vale and you don’t pay your rent, the landlord comes round and puts you in prison. If you do pay the rent, the policeman comes round and asks you where you got the money from.” – Sutherland Flece, 1938.

While Maida Vale soon fulfilled the Church Commissioners’ expectations and remained solidly middle class, it was never wholly respectable. The area was renowned for its spivs, con-men and kept women.

“Biddulph Mansions is tenanted by ladies who would invite anyone to tea with them.” declared an outraged lawyer in 1912. The New Statesman described “Dusk on a wet Sunday, and the smoothies and the spivs come West from Maida Vale. Some in their Packards…some with their women, a little fleshy, with heavy brass jewellry”. Early feminist campaigner, Vera Brittan (left), ran into trouble with her Bloomsbury landlady who did not approve of the late hours she and her flatmates were keeping. Writing in “Testament of Youth” she says that her subsequent move to Maida Vale (Wymering Mansions) could not have done more to confirm her landlady’s suspicions.

Irene Handl, the character actress, was born in Leith Mansions in1901. She recalled that “respectable people didn’t live in flats. A lot of them were occupied by what they used to call actresses but were really tarts, ladies who’d been what they called installed.” Canadian author Robertson Davies shared a flat with “two other fellows” in the same block just after he graduated from Oxford in 1936. He described the area as a “pretty scruffy district because a lot of harlots lived in Maida Vale”.

Downton Abbey’s Lady Edith Crawley (pregnant but not married) explained to her Aunt why she couldn’t keep her baby:‘I don’t want to be an outcast. I don’t want to be some funny woman living in Maida Vale that people never talk about.”

Always slightly less than respectable, Maida Vale played host to an outbreak of tabloid hysteria leading to a police raid on Ashworth Mansions in 1919. The Daily Dispatch claimed that it had received information that “gambling houses were beginning to flourish in St James, Mayfair and Maida Vale” and that officers’ wives were losing upwards of £200 per night. “Women”, it fumed, are “always the worst gamblers for they never know when to stop. They sit over the tables feverishly staking money… We advise the authorities to do something drastic in the matter.”

29 year old Robert Felkin rented flat x. He described himself as of indpendent means but was, in fact, an undischarged bankrupt. He let his flat for the evening to Reginald Sebright, a former lieutenant in one of top regiments. Sebright had been invalided out of the army and now ran illegal cards games in which he cheated young officers out of their money. Sebright brought with him a private in the Grenadier Guards, who served drinks and kept the door wearing kahki, and a lady called Madeline Wyatt to run the bank. When the police burst in at 7.40pm, they found four men and five women seated around an oval, baize covered table in the drawing room surrounded by a number of empty champagne, whisky and soda bottles. A total of £741 was found in the flat including £336 in the ladies’ dorothy bags.

The nine players were bound over to keep the peace. Sebright was jailed for three months and Felkin for two.

First residents

We know quite a lot about the first inhabitants of Ashworth Mansions from the details of the 1901 Census. Then, as now, they were a fairly mixed group of professional people from all over the world. These pioneers comprised solid middle class clerks, reasonably successful theatrical people, many widows, a few bankrupts but just 14 children. They were well looked after by a total of 45 (all female) domestic servants. Most flats had just a maid/cook although others had two – generally when a child was about and a governess or nursemaid called for.

A team of three liveried caretakers (messrs Garrod, Taussou, Davis & families) looked after the premises. Porters were typically allowed two rooms and paid about £1 a week. The Ashworth Mansions team did not get along. Garrod and Davis were summoned before Marylebone magistrates for assaulting each other. The judge said that flat life was clearly not very desirable and the trivialities that people quarrelled over were extraordinary. People who ought to know better seemed to think that just because they rented a flat the whole of the passages, which were for the use of everybody, should be controlled and used by themselves alone.

It is not clear where the porters lived and which passage they fought over. But there was a full time estate manager in what is now Flat One. The porters would normally have been available to tenants from 8.30am until 11pm. The maids would have put a dust pail on the tradesman’s lift by 9.30 each morning. The Porter would remove it and hoist up a day’s worth of coal in return.

Managers were advised that porters be “allowed light and coals, otherwise there may be complaints from the tenants. The porter is an important person, and a great care should be exercised to select a suitable man. So much depends upon him that it is advisable he should be well paid, and allowed a chance of making a little money by doing odd jobs for the tenants. It is a mistake to bind him down so as to prevent this. He represents the owner and pleasant relations between him and the tenants should be maintained.”

Of the 60 households counted by the census, 21 were wealthy enough to live on their “own means” without declaring an occupation or profession. Of the rest, the census recorded: three engineers (2 civil, one mechanical), three retired sea captains, three financial agents, one priest (orthodox), one hotel manager, one jewellery manager, two journalists, one life insurance officer, one barrister and three clerks (one solicitor’s, two barrister’s), one printers’ agent, one private secretary, one publisher, one secretary and one assistant sec to public companies, two merchants (one tea, one wine), one theatrical manager, one actress, one singer, one high school teacher, one architect, one painter, one author and one doctor.

Ashworth Mansions was solidly middle class. Looking at family background, 35 heads of family can be traced back to childhood via the Victorian censusus and 29 these grew up with one or more servants in the family home. This was the traditional Victorian marker of the middle class. Of those with working class backgrounds most were sons of small business people – farmers, iron founders, inn keepers etc who employed staff.

Notable early residents

Charles Booth noticed that the Maida Vale flats were filling up with (respectable) theatical types and there were plenty living in Ashworth Mansions in 1901. Among them was the Australian soprano Rosa Bird (flat 24) who came to Europe to study under Mme Marchesi and quickly became a society leader. She headlined a special concert in front of a “large and distinguished audience” at the Royal Albert Hall in aid of a fund for the benefits of the Widows and Orphans of Her Majesty’s Colonial Forces in the Boer War. She reportedly sang “O for the wings of a dove” with “some effect”. Rosa Bird subsequently married very well and (with her husband soon dead) lived stylishly in Chelsea. She hosted a party at which Prince Christian (Queen Victoria’s son in law) honoured Lord Kitchener on his retun from South Africa. Later she travelled the world as Mrs Arthur Popplewell singing at charity events and doing good works. During the Great War she converted her home into a hospital for injured Australian officers and was dubbed “the Australian Nightingale” by the Daily Mirror.

Another singer, Helen Jaxon, lived at flat 4 with her parents, Louisa and John, a retired sea captain. Helen “was the owner of a sympathetic soprano voice and a good deal of refinement of style” and was a favourite of Henry Wood who cast her as a Rhine Maiden. “No wobble, dead in tune”, he declared.

Felix Mansfield lived at flat 31 with his wife and three grown up children. Born on the island of Heliogoland, at that time a British possession, Felix managed the career of his brother, Richard Mansfield, “the greatest Shakespearean actor of his generation.” Another theatrical manager was Frank Shackle (flat eight) who changed profession after his stock exchange firm failed in 1898. He briefly looked after the career of Mrs Patrick Campbell, the most famous actress of her generation for whom GB Shaw wrote the part of Eliza Dolittle. Shackle broke to her the news of Mr Patrick Campbell’s unfortunate death in the Boer War in 1900.

Campaigning journalist Sydney Paternoster (married, flat 29) worked with Roger Casement to expose the atrocities committed on the rubber plantations in the Putamayo district of Peru. Rosa Leo, flat 45, cast aside an earlier career as a singer to devote herself to the womens’ movement and taught public speaking to suffragettes. There was a lot of sufragette activity in Maida Vale; one branch of the 1910 Womens Suffrage Pilgramige commenced from Elgin Avenue.

Meanwhile, residing in Flat 35 was Leonard Smithers (left), Oscar Wilde’s publisher who moved downmarket to Ashworth Mansions from his grand house in Bloomsbury with his wife and young son following his bankruptcy. In his favour, Smithers “single handedly saved the modernists” by publishing the Ballad of Reading Gaol but by common consent he was “a most disreputable man” and WB Yeats refused to meet him. His reputation was for deflowering young girls. Oscar Wilde said “He loves first editions, especially women: little girls are his passion.”

Meanwhile, residing in Flat 35 was Leonard Smithers (left), Oscar Wilde’s publisher who moved downmarket to Ashworth Mansions from his grand house in Bloomsbury with his wife and young son following his bankruptcy. In his favour, Smithers “single handedly saved the modernists” by publishing the Ballad of Reading Gaol but by common consent he was “a most disreputable man” and WB Yeats refused to meet him. His reputation was for deflowering young girls. Oscar Wilde said “He loves first editions, especially women: little girls are his passion.”

Charles Schuppisser, piano manufacturer and fraudster, rented flat 30 with his wife and baby son. He wasn’t at home on the night of the census. He was on remand charged with selling pianos he didn’t own. The prosecution alleged that Schupppisser had married in haste as his business declined and transferred all his assets to his wife to hide them from his creditors. Mr and Mrs Schuppisser were divorced in 1907.

While Smithers and Schuppisser passed through Ashworth Mansions on the way down, Arthur Paine Garratt (Flat 27) was heading in the opposite direction. Born in Lambeth, Garratt was a portrait painter and engraver who enjoyed considerable success and was commissioned to paint many of the leading people of his time including Rodin. One of his paintings still hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

While Smithers and Schuppisser passed through Ashworth Mansions on the way down, Arthur Paine Garratt (Flat 27) was heading in the opposite direction. Born in Lambeth, Garratt was a portrait painter and engraver who enjoyed considerable success and was commissioned to paint many of the leading people of his time including Rodin. One of his paintings still hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

Then as now, the residents came from the four corners of the world, reflecting London’s status as the capitol of the largest Empire the world ever saw. They came from the colonies, from the new world – the Watt family in Flat 21 were Australian; and from Europe, mainly Italian, French and Russian. The Guttari’s in Flat 26 were Italian; Russian financier Dmitri Tchernine lived with his French wife in Flat 11; and Russian born priest Nicholas Preobranensky was in Flat 25.

Of the second group identified by Booth, the Jews, there is less indication. Maybe Joseph Le Voi, a cigar merchant in Flat 66, although he was married in church. Or Peter Berchilli, manager of the Bristol Hotel, who lived in Flat 74. Religion was not a question on the UK census until very recently.

And what of kept women? Well, twenty-two year old actress Rosa Dare lived in flat 82 but has left no trace in the records of the London stage….

Other notable early residents of Ashworth Mansions included:

George Mozart (Flat 14) – one one of the most popular variety artists of his day was living in Ashworth Mansions in 1910. He began his career at the age of nine, playing the side drum for 1/- a night at the Theatre Royal, Great Yarmouth and ended it with character parts in B-movies such as 1936’s Phantom Ship starring Bela Lugosi. In between, he entertained audiences with an act involving mimicing a whole series of people without changes of props or costumes.

William John Locke (Flat 72, right) – the successful and much loved author of “Ladies in Lavender”, Locke began his career as secretary of the Royal Institute of British Architects

E C Bentley (Flat 43, left) – the father of the modern detective novel and inventor of the Clerihew who moved to Ashworth Mansions on his retirement from the Daily Telegraph in 1936. Bentley is best known for “Trent’s Last Case.”

Vladimir “the Wolf” Jabotinsky (Flat 16, right) – journalist and jewish patriot, Jabotinsky lived in Ashworth Mansions in 1918 prior to leaving to fight the Ottomans in Palestine with the Jewish Regiment of the Britsh Army

Fanny Howie (left) – Acclaimed Maori singer also known as Princess Te Rangi Pai, Howie arrived in London from New Zealand and lived in Ashworth Mansions from 1901. Click on the photo to hear her most famous song.

Dorothea Sharpe – one of Britain’s greatest ever female painters was living in Flat 91 in 1914. She shared the flat with Elizabeth McNicol, a noted Canadian artist who painted Sharpe sitting on their chintz sofa (below). Sharpe, herself, was hugely influenced by Monet and “perhaps no other British artist has painted the joy of childhood as charmingly,” says Sothebys. Sharpe’s paintings now sell for up to £100.000 each.

William Cecil Jeapes – the original projectionist at the Empire Leicester Square, Jeapes founded the Topical newsreel company which, at its peak, reached an audience of 5m weekly with exclusives including the signing of the Versailles peace treaty, the first film taken inside 10 Downing Street and the first film shown publicly of the excavations at Tutankhamen’s tomb.

Marie de Lex Fatimeh Vanderbillt Allen (Flat 44) – runaway great grand-daughter of the American billionaire railroad entrepreneur came to Ashworth Mansions in 1908 following her bigamous marriage to James Coates, a valet.

Edward Hutton (Flat 32) – pioneering travel writer and founder of the British Institute in Florence lived in Ashworth Mansions in the 1930’s.

Daily life in 1901

The men could easily find their way into town in the morning. Although the tube wasn’t opened until 1915, the horse omnibus company operated a regular service down Maida Vale with routes to the City, Victoria and Charing Cross mirroring the modern day 98, 16 and 6. The omnibuses did not leave Kilburn until around 8 in the morning as Edwardian business men did not need to get to work before 10.

If the omnibus did not suit, Ashworth residents could walk down to the Underground at Edgware Road or the overground at Kilburn High Road – then known as Kilburn and Maida Vale station. Alternatively, there were plenty of cabs to hire from Elgin Mews North and South.

The mistress would have assisted her maid with some light duties such as polishing the silver. Shopping was necessary daily in the absence of refrigeration and the wives had good selection of local shops. The parade on Elgin Avenue contained a grocer, fruiterer, fishmonger, cheesemonger, tobacconist, wine merchant, chemist and stationer. There was even a cow-keeper (for fresh milk) where the underground station is today. Purchases were usually delivered.

The servants stayed at home, dealing with tradespeople, cooking and cleaning. Deliveries were made at the back of the flats where “trademans’ lifts” winched coal and other commodities up to the balconies adjoining the original kitchens. The voids resulting from their removal can still be seen. The garden, although advertised as “landscaped”, was probably more of a yard although by the second world war it contained a tennis court.

Original layout

Originally, all the flats in Ashworth Mansions had two reception rooms – a dining room and parlour (normally with piano) – facing the street. These rooms had decorative ceilings and some still remain today. Almost all had three bedrooms.

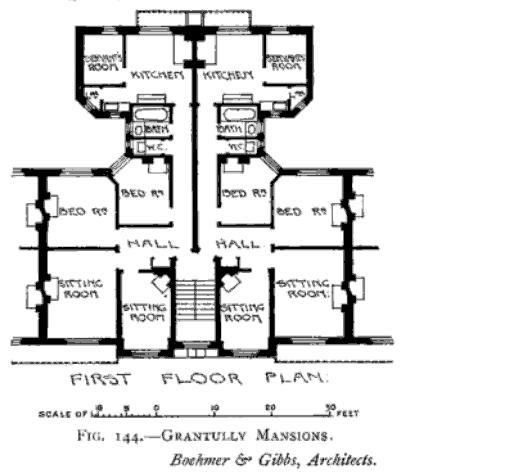

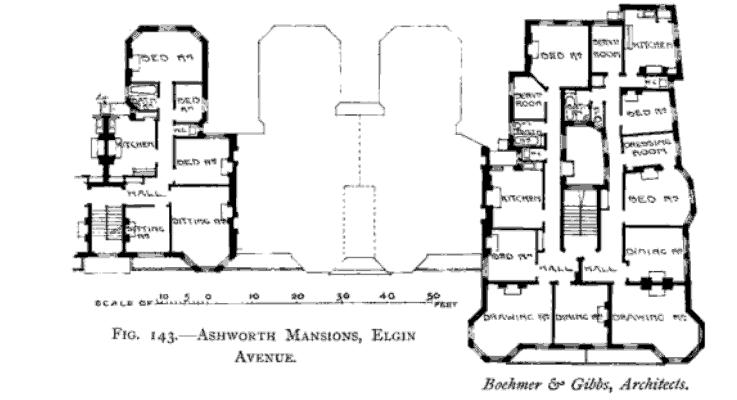

The Grantully Road flats had their kitchens and servants quarters at the back, overlooking the garden. Maids lived in a small room next to the kitchen which today is often knocked through to make a big kitchen/diner or used as an ensuite bathroom. They would have used the kitchen – with its fire – as a sitting room. All rooms had a fireplace except the servants’ ones. Sydney Perks, an architectural critic writing in 1905, criticised the placing of the stairwell at the front of the block where it takes up space that could more valuably have been used for living accommodation and he was not at all happy with the placement of the maid’s room where “the slops must be carried through the kitchen every morning”. But he liked the attempt to give th e flats “a good hall but it is dependent on borrowed light.”

e flats “a good hall but it is dependent on borrowed light.”

Most of the Elgin Avenue flats were built with the kitchen in the middle, the servant’s room towards the rear, opposite the bathroom, and the best bedroom at the back, overlooking the garden. Perks praised the large kitchens but criticised the architects’ decision to run the corridor down the centre of the flats, thereby creating a large amount of external wall.

The largest flats, occupying the two extended wings of the Elgin Avenue block had similar arrangements to the Grantully ones, but with larger rooms and an extra dressing room and WC. Perks was, no doubt, delighted that these two blocks, at least, had the stairs in the right place – in the centre of the block with windows giving onto a lightwell – although he had the grace to recognise that “it is impossible to get an ideal plan with about five roms in a second class neighbourhood and make the scheme a financial success.”

Internal decoration would have been rather sombre to contemporary tastes (see the original stairwell wall paper left) with much dark brown mahogany furniture. In contrast to modern, minimalism, pictures would have covered almost every inch of wall space.

Internal decoration would have been rather sombre to contemporary tastes (see the original stairwell wall paper left) with much dark brown mahogany furniture. In contrast to modern, minimalism, pictures would have covered almost every inch of wall space.

Perks advised would-be flat builders to concentrate on the best locations. While speculators could make more money building houses in poor areas than rich ones, the same was not true for apartments. There simply was no demand for them away from the more fashionable residential quarters. Maida Vale was just about acceptable but Clapham was not.

Historically, about half the flats in Ashworth Mansions are served by a communal heating and hot water system that was installed after the second world war. Perks would have disapproved.

“Many managers say that … hot water supply is a constant cause of trouble and annoyance. Two tenants will complain at the same time, one saying the water is too hot, and the other that it is too cold. The less [the manager] undertakes to do, the fewer excuses there will be for complaints, and the tenants of the flats do not hesitate to complain upon the slightest cause. Generally, the advice of the managers and owners is, Do not do it.”

He also advised against communal gardens. For one, they take up valuable space that could be built upon for a profit but worse “the tenants meet constantly, and there are numerous complaints, petty jealousies, and a thousand and one annoyances in consequence. The manager of the flats often has an unpleasant time during the summer. It is far better that tenants should remain strangers.”

With direct access to its lovely garden, the basement flats in Ashworth Mansions are much in demand today. But Edwardians were not so keen. Perks advised, “ It does not pay to build a basement or “lower ground floor” suite … They are bound to be dark, the front rooms are overlooked from the street…and there are other objections to them. If a basement is to be built there are other ways of using it … the space may be used for store-rooms or extra rooms for the servants.” Today, there are two flats at the foot of each stairwell. One of which is numbered “a”. The “a” numbered flat was not originally let but must have been used for storage and, possibly, to house the porters.

Flying bomb strikes Ashworth Mansions

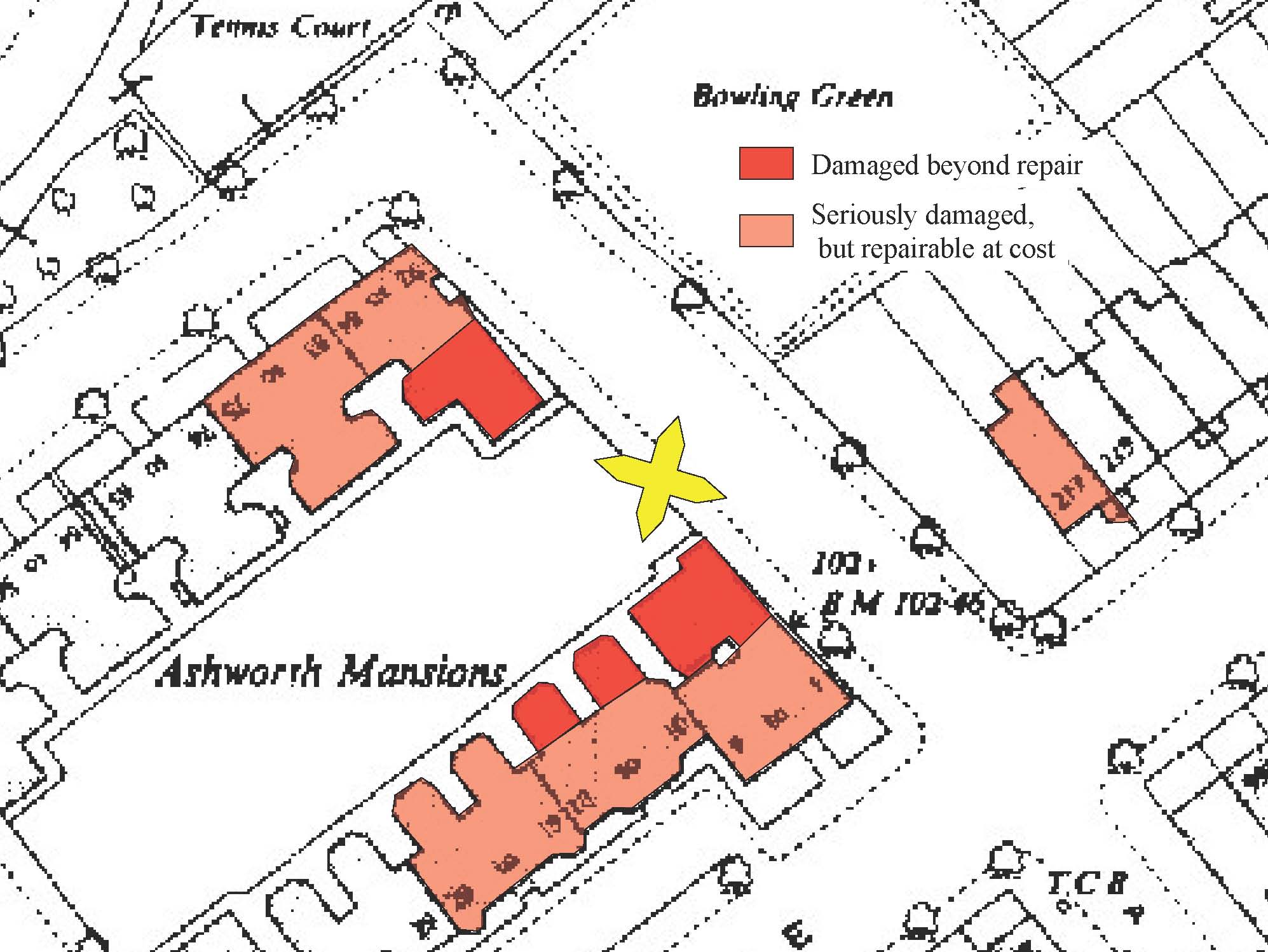

The worst day in Ashworth’s history was 23 June 1944. A V1 flying bomb struck Ashworth Road just outside the rear of block one devastating an area 250 foot square. You can see the point of impact marked with a yellow cross on the London County Council bomb damage map above. Six people were killed and 13 seriously injured. The dead included a nine year old girl and four pensioners:

Teresa Ferri, Age 9, Daughter of Romolo and Adele Ferri.

Benjamin Lewis, Age 77, Husband of Cissie Lewis.

Cissie Lewis, Age 65, Wife of Benjamin Lewis.

Elizabeth Nona James, Age 66. Daughter of Peter and Sarah James, of St. Helier’s, Wellingborough, Northamptonshire.

Theodore Lazaroff, Age 31, Husband of Isobel Lazaroff.

Hannah Anne Lee, Age 68, Daughter of the late Richard and Elizabeth Webber; wife of Daniel Lee.

The map shows that much of the estate was seriously damaged and only block 5 (corner of Elgin Avenue and Biddulph Road) was left inhabited for the rest of the war. Major rebuilding was required as you can see from the photographs. The landlords of the time went against Sydney Perks’ advice and took the opportunity to install communal hot water and central heating for those blocks shaded.

The summer of V1 bombings was a particularly depressing time for Londoners. Many had assumed that, following D-Day and the invasion of France, the worst of the war was behind them. But the rain of flying bombs in the summer of 1944 brought death and destruction to many parts of London. The bombs themselves were fitted with a primative device that measured how far they had flown and cut off the petrol supply once the target was supposed to have been reached. With fuel cut off, there was a sudden silence and those on the ground knew that they had 15-30 seconds to seek shelter. You can read Martin Clements detailed account of the flying bomb attack including eyewittness accounts.

The summer of V1 bombings was a particularly depressing time for Londoners. Many had assumed that, following D-Day and the invasion of France, the worst of the war was behind them. But the rain of flying bombs in the summer of 1944 brought death and destruction to many parts of London. The bombs themselves were fitted with a primative device that measured how far they had flown and cut off the petrol supply once the target was supposed to have been reached. With fuel cut off, there was a sudden silence and those on the ground knew that they had 15-30 seconds to seek shelter. You can read Martin Clements detailed account of the flying bomb attack including eyewittness accounts.

Ashworth Mansions after the War

Owner occupation of flats is a relatively modern phenomenon in London and the mansion blocks of Maida Vale were built for the rental market. Following their construction, the blocks were gradually acquired by a small number of large property companies whose objective was to make a steady return from property management. But over time, the return from investments in residential property declined as a combination of low returns, ever growing investment requirements and legislation controlling rents reduced the appeal of the business. From the 1960’s, the large property companies such as London County Freehold, operator of the KeyFlats empire, began selling their blocks to invest in more exciting asset classes, notably commercial property at home and overseas.

Following Harold Wilson’s rent act of 1965 which introduced swingeing controls on rent increases, flats were worth 40% more for sale than as rental investments. The only sound strategy for the freeholder was to renovate the block and sell long leases on the flats to the residents although some property companies overlooked the part about renovating the building first. There were 50.000 flats in 1.600 purpose built blocks in London in 1966. By 1992 only one third of these were still rent controlled.

Freshwater, owner of Ashworth Mansions, stood against the tide, still believing that good returns could be made by aggressively using the provisions of the Rent Act to raise rents by more than inflation in the more desirable areas. Nevertheless, Ashworth’s leases were finally sold in 1987, followed by its freehold (to its flat owners) in 1991.

The flat owners inherited an estate debilitated by years of under-investment. A programme of major works ran from 2001 to 2007. Now completed, this has returned the blocks to something approaching their original standard.

At the beginning of the 20th Century as at the outset of the 21st, Ashworth Mansions presented its residents with what they valued most. To their minds, as to ours, convenient living, a central location and a modest dash of class more than outweigh the hurly burly of communal living.

Any comments? Contact editor@ashworthmansions.com or leave a message below

Error in your text.

“Alfred Paine Garratt (Flat 27) should read: “Arthur Paine Garratt”

Arthur was the third child to James Sheridan Garratt and Mary Elizabeth Nicholls.

Arthur didn’t meet his uncle Charles Turnley Garratt, who emigrated to Australia in 1867.

It is my understanding that Arthur’s paternal Grandfather; James Garratt, was a Solicitor in Fleet Street, London. (1841 London Census)

My late mother was a descendant of Charles T. Garratt.

Sorry, it was indeed Arthur Garratt that lived in Ashworth Mansions.

In 1901, Arthur Garratt was living in Fentiman Road, Kennington with his parents. His father was a bank clerk.

First para of last section should read “London County Freehold and Leasehold Ltd” (for whom I worked 1969 to 1971.

Thanks for the information on the singer Rosa Bird (Mrs Arthur Popplewell) who fits into my research as a benefactor and volunteer of the Australian Voluntary Hospital in WW1. I am trying to find out what her given names were – very annoying that archaic practice of using the husband’s given name!

Hello. Rosa Bird was the stage name of Josephine Sarah Popplewell (nee Jacombs), born December 11, 1866 in Sydney. Her husband (Arthur henry Popplewell) died August 13, 1894 in country NSW and she left Australia for England sometime soon between March 1895 (her farewell concert in Sydney) and March 1897 (when it was reported that she sang in a concert in London).

She was my Great Aunt.

I have a VERY large file on her WW1 activities from the National Archives in Australia

Regards, Phil Jacombs

Sorry – you can contact me via email: philj@areserve.com.au

This is a truly fascinating history – it must have taken a huge amount of work.

I’m currently trying to do some similar research into the mansion block where I live. Do you have any advice on good sources to use? I’m particularly interested to know where you found the advert for renting the flats.

Any tips you could offer would be much appreciated. Many thanks.

Lucy

Thanks for the kind words.

Most of the history section is culled from the daily newspapers, mostly the Times, although the photos of bomb damage came from the Mirror’s archive.

The census was extremely helpful, of course. But also a very thorough investigation of the life and times of builder Edward Jarvis Cave published by the Camden Historical Society.

Geoff

That’s brilliant Geoff, thank you so much for your help.

I remember my Aunt and Grandmother (who lived in Ashworth Mansions)arriving at our flat in Biddulph Mansions covered in dust with coats over nightclothes I think. I was two and three quarters. Later they moved into 34 Ashworth Mansions and I have the list of kitchen things provided by the authorities and the price was £16.0s.1 1/2p

Does anyone have any information as to how some of the metal balconies at the rear of some mansions blocks in Maida Vale came about?